Emergent language: working with spontaneous language

Danny Norrington-Davies researches the strategies that experienced teachers use when working with emergent language – that produced by students in real-time interactions.

Emergent language is unplanned language that arises spontaneously during genuine interactions in the language classroom. It includes errors or communicative breakdowns produced by students, but it can also be language that teachers or learners judge to be in some way new, interesting or good to share, or language that might require some modification. This can be done by highlighting useful language or offering extensions or alternatives to the forms that the learners produce.

Why should teachers work with emergent language?

Research, eg by Nina Spada and Eun Young Kang and her colleagues, provides evidence that a combination of language-focused and meaning-focused learning leads to greater success for students than a focus on only one or the other. There is, therefore, a strong rationale for working with emergent language in the classroom, as the meaning-focused work comes through the interaction, and the language work is done in feedback. Rod Ellis supports this idea, but also suggests that when learners become aware of a gap during their L2 performance which prevents them from expressing what they want to express, they are sensitised to attend to any input containing the forms they need. This can be done through corrective feedback, amongst other responses, and a number of meta-analyses (eg by Alison Mackey and Jaemyung Goo and by Shaofeng Li) have reported that corrective feedback (the type of emergent language work which has been most studied) has a sizable positive effect on L2 learning. According to Éva Illés and Sumru Akcan, encouraging and exploiting naturally-occurring language also has additional benefits, as it enables learners to experiment, express their own meanings and find their voice.

However, little concrete guidance has been published on working with emergent language, and there is little published research on how teachers currently work with it in lessons generally. Therefore, my colleague Nick Andon and I set out to research this key area. We did this by observing and recording lessons taught by experienced teachers at a private language school and an ESOL college in London, UK, and noted what the teachers did.

How do experienced teachers work with learner language?

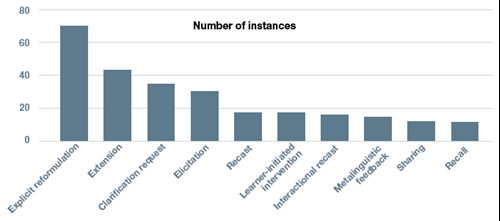

The following list shows ten different ways in which the teachers intervened and worked with emergent language during interactions with their learners. Note that many of the terms used below, eg recast and clarification request, have been used in previous studies, but we believe that the terms interactional recast and recall are new.

- Explicit reformulation (live or delayed): Explicit reformulation refers to a clear and overt provision of an alternative form. As the teacher provides the new form, they clearly indicate that what the student said was inaccurate, inappropriate or could be more natural (eg You wouldn’t say it like that, it’s ..., It’s not really ..., it’s ...) before providing a more suitable or effective form.

- Recast: Recasts involve the teacher’s reformulation of all or part of a learner’s utterance, minus any indication of error, immediately after the learner produces it. Recasts are generally implicit, in that they are not introduced by phrases such as You mean … or You should say ... . A recast could be a sound, word, phrase or full utterance.

- Teacher clarification/confirmation request: A clarification request indicates to the learner that their utterance has been misunderstood by the teacher or possibly another learner. A clarification request includes phrases such as What do you mean? A confirmation check indicates that an utterance has been only partially understood or the teacher is unsure, eg Are you saying that …? or So you mean ...?

- Metalinguistic feedback: Metalinguistic feedback uses grammatical metalanguage to provide information about the nature of the error or utterance, eg What type of word goes here? or What form of the verb do you need? It is often used to elicit a more well-formed utterance and can be immediate or delayed.

- 5 Elicitation: Elicitation refers to techniques that teachers use to directly elicit the meaning, usage or correct form from the learners, eg by asking clarification questions, strategically pausing to allow the learners to reformulate their utterance, putting utterances on the board with blanks or errors, or by using gestures. Translation can also be used, eg How do you say that in Thai? Elicitations can be live or delayed.

- 6 Extension: Extension refers to instances when teachers elicit or provide alternative ways of saying the same thing (eg stop them cheating / stop them looking up the answers). It also includes examples of teachers providing related meanings (woke up early / got up early) or similar patterns in some way related to the original utterance (stop them cheating / talking to their partners / checking their messages).

- 7 Interactional recast: In an interactional recast, the teacher provides a more appropriate form whilst maintaining communication or extending the communicative turn, eg Oh, so you had to hand them in? What happened after that? There is no indication there is an error, but unlike a recast, the teacher responds to the meaning and keeps the communication going.

- 8 Recall: A recall is a form of elicitation that refers to lexical items or forms that have been explored or taught in previous lessons, eg Do you remember the word for …? or What was the word we used for that?

- 9 Sharing: Sharing refers to instances where the teacher collects examples of interesting or useful language from a student and shares it with the rest of the class. This often occurs after pairwork or groupwork or task-preparation stages, or because the teacher suspects that the other learners did not pick up on the item.

- 10 Learner-initiated intervention: Learner-initiated intervention refers to instances where a learner asks for help with a word or phrase, or indicates that they are unsure of how to complete their utterance, eg Teacher, how do you say …?

The results

As can be seen in the table below, the most common form of intervention was explicit reformulation, which suggested that experienced teachers believed that it was important that the learners paid conscious attention to the language work that followed interaction. We also noted many instances of clarification requests, which demonstrated that the teachers felt that it was a good idea to prioritise language that might lead to misunderstanding, rather than focusing only on surface errors such as -ed endings or third person -s, for example. We also saw teachers building on the language the learners used by offering extensions. This shows that they were interested in giving the learners options and building on their lexical awareness, rather than only focusing on errors. It was interesting, though, that we saw comparatively fewer recasts than have been observed in other research.

An interesting finding was that a number of teacher feedback turns involved more than one type of intervention. In the following example (Extract 1), observed during a discussion on the use of mobile phones in class, we see that the teacher makes a clarification request as they are not sure what the learner means. When the learner explains, the teacher takes the opportunity during the pause in the meaning-focused interaction to provide some explicit reformulation. This is then followed by offering alternatives through an extension, thereby extending the learner’s lexical range relating to an item they naturally understand.

L3: Maybe students are not curious ... eh ... curious.

T: What do you mean? (Clarification request)

L5: They must control themselves.

T: I think, maybe ... curious, it could be curious, but I think ‘they’re not interested in the lesson’, or ‘they’re not focused’ (long pause) or ‘they’re not paying attention’. (Extension)

Extract 1

The next example (Extract 2) shows another combination. In this transcript, we see a Bangladeshi learner in an ESOL class describing a childhood memory of her cousin reaching for a guava. When the learner is unable to recall the word roof and indicates that they would like assistance (learner-initiated intervention), the teacher provides an explicit reformulation. The teacher then quickly checks understanding through a confirmation request before the learner carries on with the story.

L7: She were on the (mimes ‘roof’) what’s that? (Learner-initiated)

L9: Roof.

L7: Roof, yeah.

L6: What mean roof? (Learner-initiated)

T: Ah, roof. OK, the roof is the top of the building (drawing a picture and writing ‘on the roof’) so if you’ve got the building here, the roof is this part. (Explicit reformulation) Is that correct, Shahida? (Confirmation request)

L9: Yes.

T: OK.

L7: Then she saw her niece on the roof and try to get guava and she asked her what are you doing there and ... but she said ...

Extract 2 (Thanks to Richard Gallen)

It is interesting to note the instance of uptake at the end of Extract 2, as the learner uses the inputted word to continue the story. This demonstrates that, rather than interrupting the flow of the conversation, as many teachers suggest, teacher (or learner) interventions in fact contribute to that flow by helping the conversation run smoothly. This is also what natural conversations, which are full of false starts, umms and ahhs and clarification requests, really look like.

As discussed above, we saw fewer examples of recasts than in other research projects. However, it was interesting to note that when we did see recasts, they usually occurred when the interaction had switched from a communicative mode to a more form-focused one. This suggests to us that the teachers we observed felt that recasts are more effective when the learners have switched their focus to form, rather than when they are done incidentally as the learner communicates. This can be seen in the transcript below (Extract 3), where a learner is describing how they used to hide phones in the school after they were banned from bringing them onto the premises. During the story, the learner indicates with a questioning intonation that they are unsure of the verb they are using (make it). Without giving any indication or suggesting there is an issue, the teacher merely recasts, or provides an alternative, more suitable, form (hide it). This is repeated when the learner mispronounces the verb when they modify their language. A few turns later, the learner describes how their school was full of phones hidden in air vents!

L2: If we want we bring it like we bring drugs or something. We hidden. We try … We have many ways to … make it? (Learner-initiated)

T: To hide it. (Recast)

L2: Hid it.

Teacher: Hide it. (Recast)

L2: To hide it.

Extract 3

A final interesting point is the number of instances where the teachers hedged when working with emergent language and offering corrections. They did not often suggest that utterances were right or wrong, or use phrases like That’s wrong or You can’t say that. Instead, they used more tentative phrases like I’d go with … or For me, this one sounds better. This suggests a desire not to impose standards, but to give the learners alternatives and improve comprehensibility. This can be seen in Extract 4, where the teacher is giving delayed feedback at the board after the learners have completed a task where they discussed whether mobile phones should be banned in the classroom. Note that this is an example of explicit reformulation and metalinguistic feedback.

T: (pointing to examples on the whiteboard) I like this one: If we didn’t use our phones, we didn’t die. You’re talking about the present but there is an element of future too, so I think you need to change this verb (points to didn’t).

L: Won’t.

T: Um, if we didn’t use our phones we won’t die? I think that’s OK. I’d go with wouldn’t. (Explicit reformuatlation)

Extract 4

As emergent language is unplanned and occurs during real-time interaction, choosing to work with it places many demands on the teacher. To begin with, it can be difficult for teachers to notice the language or the gap in the learner’s linguistic knowledge. They then must decide whether it merits treatment and determine what the best course of action is. The teacher must also quickly identify alternatives or ‘correct’ versions, and then consider how they will involve the learners in the intervention. As working with emergent language is a difficult skill, in an article in the next issue of ETp, Richard Chinn will outline some tips and techniques for helping teachers to develop their ability to work with it.

The research described in this article was conducted while I was seconded at King’s College, London. I would like to thank Nick Andon for this opportunity.

Ellis, R ‘Focus on form: a critical review’ Language Teaching Research 20 (3) 2016

Illés, É and Akcan, S ‘Bringing real-life language use into EFL classrooms’ ELT Journal 1 (1) 2010

Kang, E Y, Sok, S and Han, Z ‘Thirty-five years of ISLA on form-focused instruction: a meta-analysis’ Language Teaching Research 23 (4) 2019

Li, S ‘The effectiveness of corrective feedback: a meta-analysis’ Language Learning 60 (2) 2010

Mackey, A and Goo, J ‘Interaction research in SLA: a meta-analysis and research synthesis’ In Mackey, A (Ed) Conversational Interaction in Second Language Acquisition: A Series of Empirical Studies OUP 2007

Spada, N ‘SLA research and L2 pedagogy: misapplications and questions of relevance’ Language Teaching 48 (1) 2015

Danny Norrington-Davies is a teacher and teacher educator at International House London. He is a keen conference speaker and the author of Teaching Grammar: From Rules to Reasons, published by Pavilion.

Comments

Write a Comment

Comment Submitted