Listening to students' spoken language

I was flicking through John Hughes’s new book ETpedia, which aims to provide English teachers with 1,000 teaching ideas, and was pleased to see some very useful teaching ideas listed under user-friendly page headers like ’10 ideas to add variety to a reading lesson’, ’10 sources of listening material’, ’10 activities using the objects around you’, and ’10 activities for the topic of food’.

But the page that caught my attention was ’10 ways to correct a spoken mistake’. While keeping it simple and easily understandable, this page was able to summarise the main issues and techniques related to correcting spoken language that we try so hard on teacher training courses like the CELTA to convey to trainees.

Hughes states:

“If you are presenting a new language item and you ask a student to produce a sentence with it in and they make a mistake, then it's clearly the right moment to correct the error.

If, on the other hand, the students are involved in a fluency activity such as a role play and you hear a mistake, you have to ask yourself a number of questions:

- Should I interrupt the students in full flow and point out the error now or do it later?

- Is the mistake something they should already know or is it something that will be dealt with at a later stage in their learning?

- Is it a mistake they are regularly making which I need to remind them about? Or is it just a slip that they have made and they will probably get right next time?

- Is it a mistake which doesn’t affect understanding? If not, is it worth trying to correct at their current level?”

It looked like before a teacher can even start to think about how to correct, they need to first of all become a multi-tasking listener.

Talking to several Directors of Studies of different language school, it became apparent that one of the main complaints that students/clients often have about their classes is that the teachers do not correct them enough.

Of course, these complaints can be attributed to two things:

1. The students/clients have a different idea of what adequate correction means and might expect a level of correction that would interfere with their fluency and language practice.

2. The teachers are really not correcting them enough.

In the first scenario, it is perhaps necessary for the teacher or Director of Studies to conduct a thorough needs analysis while addressing the student’s expectations of how their language ability can be improved and what they consider to be ‘mistakes’.

However, when I observe less-experienced teacher trainees doing their teaching practice, I often find that the second scenario is often true. Correcting students is tough, and this is made even tougher if you come from a culture that frowns on direct confrontation and prides indirect criticism often disguised as jokes and irony.

However, when I observe less-experienced teacher trainees doing their teaching practice, I often find that the second scenario is often true. Correcting students is tough, and this is made even tougher if you come from a culture that frowns on direct confrontation and prides indirect criticism often disguised as jokes and irony.

Before deciding upon which methods of correction to use, one has to first hear the mistake and remember it until the correction takes place. In the meantime, one has to ask oneself the four questions listed by Hughes (in bold above). It’s a lot for a new teacher to do. And this is why I offer the following tips to those struggling to deal with spoken language correction.

You can either correct students on the spot as you hear the mistake being made, or you can make note of the mistake and do a delayed correction slot at the end of the speaking activity. Some prefer to do delayed correction slots when students are deeply involved in group tasks as this avoids interrupting the flow of conversation and also allows the other students in the class to learn from the mistakes made by their classmates.

(Please note : For the purpose of this blogpost, I have chosen not to make a clear distinction between ‘mistake’ and ‘error’ although I know that some schools of thought prefer to distinguish between the two.)

1. Carry a notebook with you at all times

In order to help you with your delayed correction slot, and to help you practice hearing the language issues that students have, you should buy yourself a nice-size notebook that you can hold in your hand and bring around with you as you observe the students in their tasks.

2. Get practice of writing down full sentences that you hear

This goes against everything we’ve learnt about note-taking in our university years when we were taught to summarise and write only the main points, dropping pronouns etc. Instead, try writing down the sentences that students say ad verbatim.

You don’t need to write down every single sentence (and you won’t be able to), but if you hear something that doesn’t sound quite right, write it down. You can examine it for what is wrong with it later.

3. Learn to listen above the buzz of multiple conversations

3. Learn to listen above the buzz of multiple conversations

When listening to groups of students involved in speaking tasks, what makes this more difficult, especially for less-experienced teachers, is the overlap of sounds and sentences that happens when several conversations are taking place all at once.

Learn to lean in while averting your eye-line so that you don’t get drawn into conversations with students and interrupting their flow. Cup your ears towards the conversation you’re listening into so as to help your concentration and focus.

With practice, you’ll notice that you’ll not only be able to pick out what is being said in one group of students, you’ll also be able to listen in to two conversations at the same time and pick out sentences to take note of!

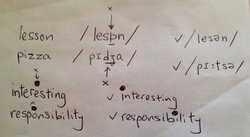

4. Learn to use the phonemic script

Knowing the phonemic script well can help you to take note of the way a student is saying something that doesn’t sound right. Use black circles or squares above syllables to signal the stress that students are putting on words or syllables.

See below for how I do it in my notes.

5. Noting different types of mistakes.

My trainees seem to find it easier to pick up on single-word-level grammatical errors, e.g. mixed up pronouns – ‘he’ instead of ‘she’, wrong past tense of irregular verb – ‘bring-ed’ instead of ‘brought’, not using the third person singular – ‘She have a lot of money’.

Problems with syntax, lexical use and pronunciation are often not picked up on, and the system of discourse is typically overlooked not just by inexperienced teachers but by teacher trainers themselves.

So here are some of the types of language use to begin practising taking notes of:

Collocational errors

- ‘He made a photo’ (instead of ‘took a photo’)

- ‘I went to the café to take a coffee’ (instead of ‘have a coffee’)

Note that some collocational errors can come from directly translating from the students’ L1.

Word order and ellipsis

- ‘It was a photo very nice’ (instead of ‘It was a very nice photo’)

- ‘He a lot eat every day’ (instead of ‘He eats a lot every day’)

- ‘Was raining’ (instead of ‘It was raining’).

Prepositional error

- ‘He took a photo on me’ (instead of ‘of me’)

- ‘We talked on the topic about homestay’ (instead of ‘talked about’ and ‘the topic of homestay’)

False friends (L1 transfer of lexical items)

- ‘He was working as a sales person. But actually, he is working as a teacher.’ (instead of ‘But currently, he is working…’ – Italian, Spanish, French and Portuguese false friend

- ‘When she graduated, she became a car.’ (instead of ‘she got a car’ – German false friend)

Overgeneralising use of lexis

- ‘My room has many small animals like ants’ (instead of ‘small insects’)

- ‘The pilot drives the plane to Germany’ (instead of ‘The pilot flies the plane to Germany’)

Pronunciation errors

- Wrong sentence or word stress; mispronouncing vowels, consonants, and dipthongs, etc.

Discourse issues especially in group tasks

- Not acknowledging or commenting on previous speaker’s point; not using linkers to help the flow or to set the scene (it’s all about helping the listener know what to expect); awkward turntaking, dominating the floor and not inviting others to join or asking for their opinions; not knowing how to ask for confirmation or clarification, etc.

Good sentences that exemplifies good use of language

- Here, you may choose to pull up good use of the target language, good use of linkers, interesting collocations and fixed expressions, complex sentence structure like passives, conditionals or relative clauses, etc. This not only helps to boost the confidence of the speakers, but also encourages other students to learn from their classmates.

As with anything, practice makes perfect.

So keep walking around the classroom observing and monitoring your students with your notebook handy and write down as many sentences as you can hear.

Soon, you will notice that your listening and note-taking ability has improved and one day, you will find yourself doing on-the-spot correction with one student in one group conversation while writing down sentences spoken by students in a different group conversation all at once.

You will then be a true multi-tasking listener!

Bibliography

Hughes, J. (2014) ETpedia: 1000 ideas for English language teachers. Pavilion Publishing.

Please note that the above book is available to purchase on our website.

Chia Suan Chong is a General English and Business English teacher and teacher trainer, with a degree in Communication Studies (Broadcast and Electronic Media) and an MA in Applied Linguistics and English Language Teaching from King’s College London.

Fascinated by the interplay between culture, language and thought, Chia is also an intercultural skills trainer and materials developer, and is now based in York.

She is also the voice of @ETprofessional on Twitter. You can find out more about her on her blogsite www.chiasuanchong.com

Comments

Write a Comment

Comment Submitted