Paraphrasing strategies: turning failure into development

You plan a lesson well, you’ve already done similar things before, you feel confident. You go into the classroom and it doesn’t work at all. Does this sound familiar? Sometimes, no matter how well we plan (and how many good questions we ask ourselves questions before setting up an activity, we can’t seem to produce the results we expect.

I was recently teaching an IELTS class when this happened, but despite the frustration, it turned out to be a great opportunity for development.

My students are aiming for an IELTS band score between 6 and 7 as they want to apply for university here in the UK. In both writing tasks in IELTS, students start their writing by paraphrasing the exam question. Paraphrasing is not necessarily something that students know how to do or transfer automatically from their first language, so it’s worth developing in class. In fact, there are a number of reasons for teaching it:

- It’s a necessary skill for academic writing and helps avoid academic malpractice.

- It’s required in the writing sections of various exams.

- In listening and reading exams, students answer questions that are often paraphrases of what they hear or read: with good paraphrasing skills, they can identify them more quickly.

- It’s an opportunity to simultaneously develop vocabulary (e.g. synonyms, hypernyms) and grammar (e.g. sentence transformation).

What went wrong

Being aware of all these reasons, I set out to do an IELTS Academic writing Task 1 with my students: they had to write a 150-word report selecting and comparing the main data in a chart. In the first paragraph, they had to rewrite the exam question: ‘The graphs above give information about computer ownership as a percentage of the population between 2002 and 2010, and by level of education for the years 2002 and 2010.’ using different words, for example: ‘The bar charts show data about computer ownership, with a further classification by level of education, from 2002 to 2010.’

I asked them to read the question, underline the key words and think about how to paraphrase it. We then built a paraphrase together and I wrote their ideas on the board. As I wrote them, I asked them to tell me what they had done, e.g. ‘use a synonym’ or ‘change the name of a country to a nationality’. I followed up by giving them another similar task sample and asked them to paraphrase the introduction individually. Despite the work we had done together, during that lesson and on a previous occasion, they still struggled to think of how to paraphrase and were unhappy with their results.

When failures like these happen, I find it useful to think of a point Judith Hanks (2017) makes when she talks about Exploratory Practice: books and articles tell us about what problems are and how we could solve them, but our main question as practitioner should be why. So why did my students struggle to come up with ways to paraphrase the exam question even though we had just practised this?

Turning frustration into reflection

Reflective practice is an important part of my development as a teacher. As Farrell and Cirocki (2017) recommend, I went through three stages: reflection-in-action, reflection-on-action and reflection-for-action.

- Reflection-in-action

This is what I thought while in the class: I believed practising paraphrasing and asking students to quickly name them would be enough for them to implement them. When they couldn’t, I started thinking about why and my immediate solution was simply to remind them of what we had just done.

- Reflection-on-action

Here is when we think retrospectively about our practice: why couldn’t they do it? I read a little more about language learning strategies and found that actually, some explicit instruction of strategies works (Oxford, 2002): it can clarify things for learners, creating a repertoire of strategies that they can draw on when writing in the future. I was worried that spending time writing down what strategies we had used might be repetitive and thought that an ‘implicit’ approach would work, but I decided to experiment with more explicit strategy teaching.

- Reflection-for-action

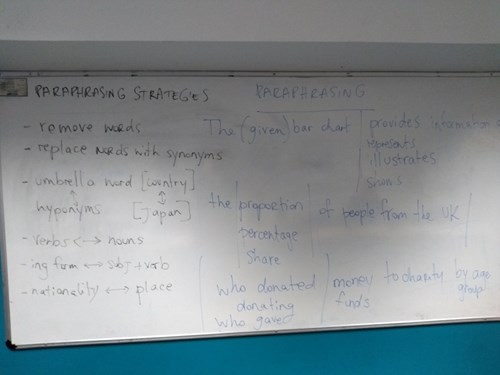

After a couple of lessons, I decided to try paraphrasing another writing task 1 as a group, only this time, I added a final review phase in which we categorised the strategies we used. In the end, it looked like this:

I asked my students to paraphrase the introduction to another task by themselves. Based on their feedback, having this list of strategies to use guided them and helped them write more successfully. We have continued adding strategies to this list whenever we have practised paraphrasing in subsequent classes and I have noticed improvements in the accuracy of their introductions.

Have you ever had a failure that turned into an opportunity for development? Please share in the comments section!

References

Farrell T and Cirocki A (2017) Reflective practice for the professional development of TESOL practitioners. The European journal of applied linguists and TEFL 6(2) 5–24.

Hanks J (2017) Exploratory practice in language teaching: puzzling about principles and practices. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Oxford R (2002) Language learning strategies in a nutshell: Update and ESL suggestions. Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice 4 124-132.

Comments

Write a Comment

Comment Submitted