Training Foreign Language Teachers: A Reflective Approach (1991)

The book I always refer to

Jason Anderson chooses his go-to title

Training Foreign Language Teachers: A Reflective Approach (1991)

Michael J Wallace

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

ISBN: 9870521 356541

It took me some time to choose this book, not because I don’t have a ‘go-to’ book, but because I have so many. If I had chosen to write this piece with a focus on professional expertise, it probably would have been Schön’s The Reflective Practitioner (1983). If my interest had been educational theory, Bruner’s The Culture of Education (1996) might have got the call up, and if I were writing with my researcher hat on, I might have chosen Dörnyei’s Research Methods in Applied Linguistics (2007) as my most regularly referenced title. However, given that the majority of my own work today falls mainly under the gamut of teacher education, I’ve chosen Wallace’s Training Foreign Language Teachers: A Reflective Approach (1991) probably because it’s the one that helped me greatly when I began helping other teachers to learn how to teach (or not). And it’s also the one I tend to recommend to those who are interested in becoming teacher educators, even today, 30 years after it was written.

Wallace’s three models for teacher education

Let’s get one negative out of the way to start with – the title. It seems to me that it should be called ‘Educating foreign language teachers’. This is because – as Wallace presents clearly and simply – teacher education is much more than just, or simply about ‘training’ teachers (see Freeman, 1989). He begins the book, in the first chapter, by making a distinction between three models for teacher education, summarised in Table 1.

|

Model |

Example |

|

1. The craft model |

Short initial training courses (e.g. for the Cambridge CELTA) are often primarily craft oriented. |

|

2. The applied science model |

Many MA TESOL qualifications tend to follow this model. |

|

3. The reflective model |

A well-developed in-service programme. |

Table 1 Wallace's three models for teacher education

Today, there are other models that we might add to this trichotomy (discussed below). However, these three are still probably the most prominent in teacher education, and still very influential on the practices of those that undergo them. To modify Lortie’s (1975) observation that we tend to teach like we were taught, it seems to me that the majority of us, when we get into teacher education, tend to try to teach others to teach like we were taught to teach. Those of us who underwent the ‘CELTA-DELTA’ type route will often adopt a craft model, including ‘demonstration lessons’, ‘feedback’ on ‘TP’ and practical ‘workshops’ on specific skills, such as checking understanding, giving instructions and correcting errors. Those who completed MA TESOL programmes will often include ‘lectures’ and (invariably written) ‘assignments’ on their own ‘programmes’, followed by a ‘practicum’ to implement the learning, often rather detached from the classroom where the received knowledge may or may not have been imparted. For those of us who reach the point of realising that neither of these models, on its own, is likely to be appropriate or adequate for the majority of teachers, Wallace’s reflective model builds wisely on the strengths of both.

While Wallace was heavily influenced by Schön’s writing on practitioner reflection (1983; 1987), his reflective model departs from Schön’s primary reliance on ‘reflection-in-action’ as the core means of professional learning (see Anderson, 2019) and manages to achieve a useful synergy between the two prior approaches and Schön’s – in this sense, I think, it is a more complete one, and has underpinned both in-service programmes and pre-service short courses that I’ve implemented on several occasions successfully (based on both feedback and outcomes).

The core of the book

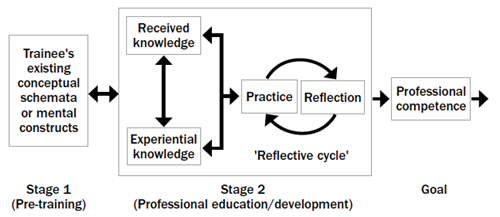

In chapters 2, 3 and 3, Wallace goes on to discuss aspects of his model in depth. In chapter two he discusses how received knowledge can be effectively imparted (e.g. practising what you preach, encouraging deep learning). In chapter 3 he provides detailed guidance on different ‘delivery’ approaches, contrasting ‘lecture mode’ and ‘group mode’ critically, offering guidance and cautions for both, and emphasising the importance of variety in longer-term and formal education programmes. Then, in chapter 4, he walks us chronologically through the stages of his reflective model (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 The Reflective Practice model of professional education/development (from Wallace 1991)

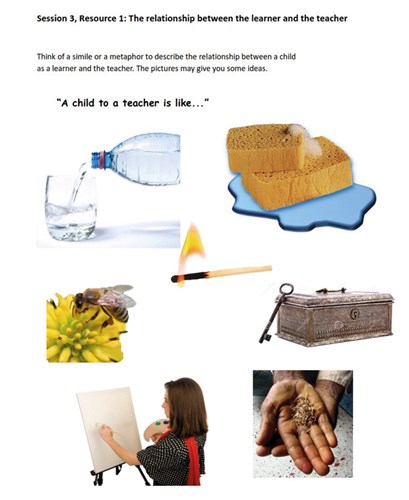

He goes into useful detail on what he calls a ‘pre-training’ stage that provides time and opportunities for teachers (pre-service or in-service) to explore their current beliefs, schemata and knowledge bases – all good advice that I have drawn upon on teacher education programmes myself (see Figure 2). As Borg (e.g. 2018) and others have observed, based on sound evidence, these beliefs are of critical importance to how we teach and need to be surfaced and explored in any useful teacher education programme.

Figure 2 Materials for teacher education that address teachers’ beliefs about learning (from Anderson & Kamaluddin, 2015, used with permission).

In chapters 5 and 6, Wallace looks in detail at two key aspects of teaching practice in teacher education that are all too often either oversimplified or overlooked today: lesson observation and microteaching. In chapter 5, he looks at several key parameters of lesson observation (e.g. data source, medium of recall, ‘interpreters’) to unearth why getting this right is central to effective teacher support during what is inevitably a stressful and complex event for the teacher involved. And in chapter 6 he unpicks microteaching, looking at the manifold ways it can be used to gradually increase the risk factor for pre-service teachers as they begin teaching practice to build confidence and understanding simultaneously. Contrast this with the ‘in-at-the-deep-end’, ‘drag and drop’ approach so often used on short training courses that can lead to more damage than learning at this critical stage in a potential teacher’s career.

The next two chapters of the book focus on supervision and assessment in teacher education, chapter 7 looking particularly at lesson observation and ‘feedback’ from the perspective of line managers (e.g. department head, director of studies) or practicum supervisors, drawing wisely on Freeman’s (1982) earlier work in this area, and ultimately recommending, where possible, a move from prescriptive supervision to collaboration within which greater teacher reflection may scaffold more extensive and sustainable learning. The rather brief chapter 8 looks at assessment, offering a useful range of tools beyond the almost monolithic written discursive assignments that tend to dominate university teacher education programmes. Many university teacher educators around the world would do well to remind themselves of the options available – assessment doesn’t have to involve setting and ‘marking’ such assignments.

The book ends with a look at course design for teacher education, drawing upon a case study of a B.Ed. type course that considers the needs of non-native teacher participants and could be useful for national pre-service programmes to prepare primary and secondary teachers. Whilst much of this chapter is fairly common sense to anyone with experience in formal education (e.g. aims and objectives, course design, etc.), the foci on progression and coherence (pp. 151-155) are useful: these important features are often lost as courses that are initially well designed get picked apart, reordered and jam-packed full of the varying, and sometimes not so helpful, input of different stakeholders.

Evaluation and critique

Unlike so many books on teacher education available today, which are either too idiosyncratic, too opaque in meaning, overly opinionated or simply one-sided in their promotion of a particular approach, Wallace is very good at steering a steady course between the options available, essentialising and conveying the ideas of others for the reader without being afraid to replace them with more pragmatic alternatives at times, based on his own extensive experience.

Possible criticisms might relate to his attempt to deal with both pre-service and in-service teacher education simultaneously throughout the book, which causes ambiguity at times, and, from today’s perspective, his focus on learning styles in Chapter 2 would likely be rejected. However, even here, his primary focus on deep versus surface learning and his choice to move the discussion on to learning strategies is further evidence of his wisdom; both have stood the test of time. Finally, his 3-model approach seems to be heavily influenced by Mary M. Kennedy’s earlier (1987) article in mainstream teacher education which promotes the same three models alongside a fourth case study model, yet she does not receive acknowledgement, even as a reference. It may be a co-incidence, of course, but including this thought allows me to promote her piece also – well worth a read!

Final thoughts

Looking back on a book that was written 30 years ago before I even started my career, I still find it a useful point of reference. However, one model that I would add onto his three, if I could, is a teacher research model – something that has gained in prominence in teacher education since the turn of the century, with action research (e.g. Burns, 2009; Smith & Rebolledo, 2018) and exploratory practice (e.g. Hanks, 2017) both becoming prominent. Lesson study (e.g. Rappleye & Komatsu, 2017) might also fall under this umbrella. These constitute a growing resource base of ‘bottom up’ approaches to teacher education that were comparatively rare when the book was written.

What impress me most about this book are Wallace’s extensive practical awareness and his ‘principled eclecticism’ (Widdowson, 1979), something that we all may benefit from in an era when models, methods and mantras for teacher education can be so dangerously circulated, liked and adopted across widely varying contexts around the world through the click of a mouse button. Referring to less principled practices, Wallace notes in his concluding remarks to the book,

‘what is truly constraining is to be the prisoner of unexamined traditions of teacher education which may never have had any real professional validity, or which may have lost whatever validity they once had through the passage of time’ (Wallace, 1991, p. 164).

I am happy to reflect that the same passage of time has not lessened the validity of his book for me.

References

Anderson J & Kamaluddin AKM (2015) Participant’s handbook: UNICEF Bangladesh training workshop on child-centred teaching and learning. Dhaka, Bangladesh: UNICEF.

Borg S (2018) Teachers’ beliefs and classroom practices. In: P Garrett & JM Cots (Eds) The Routledge handbook of language awareness (pp75–91). London: Routledge.

Bruner J (1996) The Culture of Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard.

Burns A (2009) Action research in second language teacher education. In: A Burns & JC Richards The Cambridge guide to second language teacher education (pp289–297). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei Z (2007) Research Methods in Applied Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Freeman D (1982) Observing teacher: Three approaches to in-service training and development. TESOL Quarterly 16 (1) 21–28.

Freeman D (1989) Teacher training, development and decision making: A model of teaching and related strategies for language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly 23 (1) 28–46.

Hanks J (2017) Exploratory practice in language teaching: Puzzling about principles and practices. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kennedy MM (1987) Inexact sciences: Professional education and the development of expertise. Review of research in education 14 133–167.

Lortie D (1975) Schoolteacher: A sociological study. London: University of Chicago Press.

Rappleye J & Komatsu H (2017) How to make lesson study work in America and worldwide: A Japanese perspective on the onto-cultural basis of (teacher) education. Research in Comparative and International Education 12 (4), 398–430.

Schön DA (1983) The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Schön DA (1987) Educating the reflective practitioner: Towards a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Smith R & Rebolledo P (2018) A handbook for exploratory action research. London: British Council.

Wallace MJ (1991) Training Foreign Language Teachers: A Reflective Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Widdowson HG (1979) Explorations in Applied Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Comments

Write a Comment

Comment Submitted