Why I teach my students how languages are learned

Is it useful for our students to learn about language learning? In this week’s blog post, Chiara Bruzzano discusses what it means to teach students how languages are learned, she suggests ideas for how this can be done in practice and lists the eight reasons why students may benefit from this.

“It’s so frustrating: I understand the rule, I can use it, but I can’t do the exercises!”

A while ago, I was teaching one-to-one courses for an educational institution. My students were lecturers and researchers. They were meant to complete a series of exercises in their own time and then use the live sessions with me as tutorials, to ask me for clarifications. Needless to say, the exercises were mostly gap-fills on grammar and vocabulary, with little to no contextualisation.

Consequently, people with brilliant minds and who were generally pretty good at English ended up wasting hours trying to think of the right verb tense to fill out little gapped sentences with very little context to go on.

Was this something that was going to substantially enhance their language learning? Doubtful. But was it something that was impacting their self-confidence? Absolutely yes.

Completing these exercises was an institutional requirement (as it often is), so I couldn’t just tell the students to not do them. What I did start doing instead, which has changed my teaching practice for good, was explain to them the relative importance of the ability to do these de-contextualised, controlled practice exercises as opposed to developing their language skills more broadly.

In the story above, I just couldn’t take seeing an otherwise brilliant student get so demoralised over something so meaningless. So, I took ten minutes out of the class to sit down with her and – in her first language (L1) so the message would come across clearly and strongly – proceeded to explain to her the basics of how languages are learned and why it really wasn’t a big deal that she was struggling with the exercises.

Explaining the basics of language learning

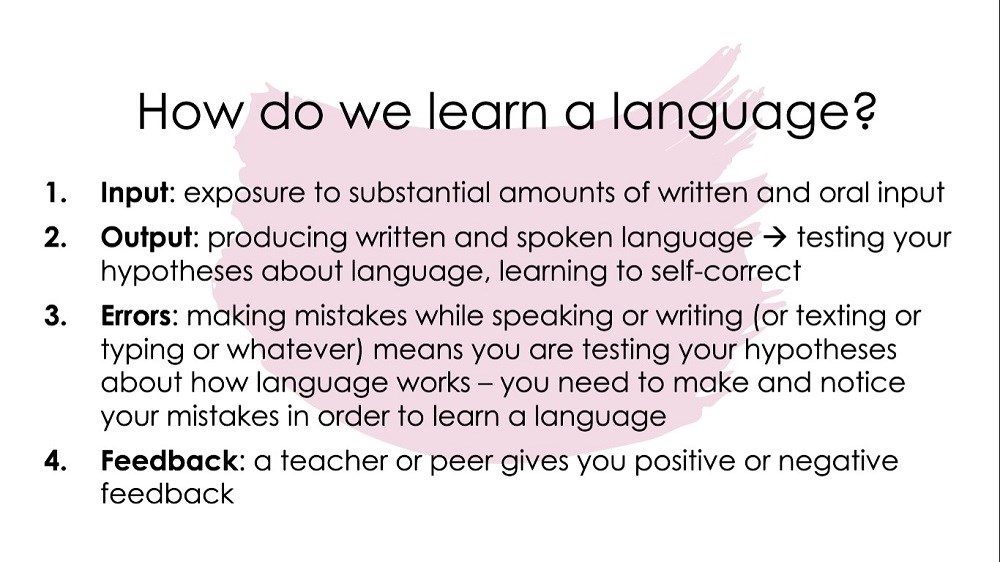

Ever since, I have incorporated the practice of learning about language learning in most of my courses. I often start with it in the first lesson of the course, with a slide like this:

This may not always be possible in the students’ second language (L2), so whenever needed, I switch to the L1 (which I use judiciously, but this is one of those cases where I think it’s beneficial).

I also talk about where students’ difficulties may originate during the course and I always make sure we discuss how they can develop their English outside of our classes based on their personal preferences and interests. I often use this video, English for beginners as a starting point for our discussions.

But why do I use precious classroom time to discuss with my students how languages are learned? Here are my eight good reasons.

1. It helps develop metacognition

Metacognition is the ability to plan, monitor and evaluate one’s performance and learning. Knowing what it means to learn a language makes it easier to plan more effectively: for example, knowing what sort of activities aid in developing comprehension skills helps learners plan what to do in their free time more strategically. Further, going back to the story of my student’s frustration, knowing that failure to fill out a gap-fill may not be as important to language learning as one may have thought can help the student monitor and evaluate their progress in a new, more realistic light.

2. It makes students feel more in control

Learning and/or acquiring a language is anything but a linear process. Students who don’t know this and expect to become proficient through a process of linear assimilation are likely to be disappointed. On the other hand, students who do know this also know to manage their expectations better and are likely to feel more in control of their learning.

3. It keeps frustration at bay

As a consequence of the point above, if we reinforce the idea that certain things take time to develop and some exercise formats may not be as crucial to language learning overall, students may revise and adjust their levels of frustration accordingly. Take, for example, the use of vocabulary in speaking. One of the complaints I hear most often from students is that they memorise and can understand vocabulary but they can’t then use it when they speak. Explaining to them the difference between passive and active vocabulary or the role of retrieval in vocabulary learning may help them understand their difficulties and be more realistic in their goal-setting.

4. It challenges widely-held learner beliefs

Who hasn’t heard things like ‘speaking English means sounding like a native speaker’ or ‘grammar is the most important thing’? These types of beliefs are widespread and can be detrimental to language learning, as students may prioritise such aspects of language learning while neglecting other potentially more fruitful activities. Discussing how languages are learned may begin to address these misconceptions. On a basic level, even discussing why you don’t ‘study’ English may be a good starting point!

5. It helps students understand what you’re doing in the classroom

Your teaching practices will be based, to an extent, on your knowledge and understanding of what it means to learn a language. While different theories exist, your teaching will at least partially reflect what you think language acquisition looks like. It is therefore important for students to know broadly what language learning means so that they understand the rationales behind your instructional activities. For example, knowing that you need to work with different English varieties rather than just ‘Standard’ British English from the outset will help students feel at ease with you using such varieties in the classroom.

6. It is key to process-based instruction

Following on from the point above, I find that discussions of what it means to learn a language are key when we implement process-based instruction, shifting the focus from the product of language learning (such as the final version of a text written by a student) to the processes behind it (such as brainstorming, planning or generating ideas for writing). I’ve personally just started running a course focused on developing the listening processes needed to cope with listening to authentic materials and have been having these discussions (though stay tuned for my upcoming blog post reviewing this experience!)

7. It builds trust when experimenting with ‘unorthodox’ methods

Have you ever tried to go into the classroom and go full-on Dogme on your students without prior notice? I’m sure this will work in some settings, but innovative programmes that deviate from more ‘traditional’ lockstep teaching often clash with students’ expectations and result in students’ resistance (Huang 2006). This can be tackled by having open and frank discussions about the reasons behind the ‘method’. This may also be the case when it comes to decisions such as ditching the textbook.

8. It allows you to co-exist with rigid contextual constraints you disagree with

If your institution expects you to use specific materials and prepare your students for specific exams, you can’t exactly refuse to do this – regardless of whether you think it will be conducive to language learning. However, I have found that introducing short moments of reflection and discussion of how languages are really learned helps students put things in perspective and it helps me feel I can live with a grammar-based synthetic syllabus (which would normally make me want to set my diplomas on fire). It also helps me fight the negative washback that comes from some discrete item tests of grammar and vocabulary.

Conclusion

So these are all my reasons for teaching students how languages are learned.

What do you think? Have you ever tried to do this? Feel free to share your experiences with me in the comments section.

References

Huang, J. (2006). ‘Learner resistance in metacognition training? An exploration of mismatches between learner and teacher agendas.’ Language Teaching Research, 10 1: 95–117.

Comments

Write a Comment

Comment Submitted